From rugged coastlines to mossy bogs and mountains speckled with heather, Ireland’s natural landscape can seem otherworldy and mystical. It comes as no surprise that it is a boundless source of inspiration for creatives, storytellers and artists. Installation-based artist Christine Mackey grew up on a farm in Co. Kilkenny, surrounded by fields, hedgerows, animals and plants. This upbringing, immersed in nature and living of the land that surrounded her - growing crops, picking strawberries, and feeding animals - fostered a deep sensitivity to the natural world in her. This connection informs her engagement through the visual arts, which explores ecology, rural life, and our relationship with the land.

Artistic Background

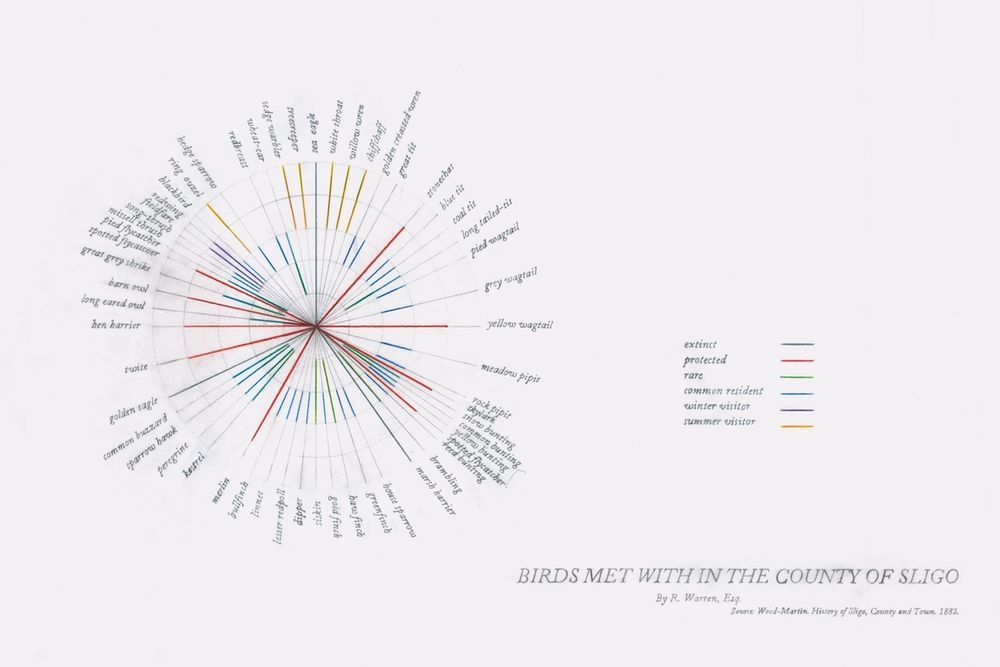

Christine’s artistic exploration of environmental themes started with a public commission with Sligo Arts Office in 2008, where she engaged deeply with a specific hydrological trajectory, the River Garavogue. Exploring the complexity of relationships across communities - both human and other-than-human that meandered through the course of this river was a formative opportunity for Christine. These long-term engagements led to a unique publication and exhibition that embodied many explorations of the landscape while tapping into people’s local knowledge, including that of walkers, residents, and fishermen.

Research as part of Mackey’s publication RIVERworks. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

In 2022, Christine was invited to develop a project under the remit of the Eco Showboat initiative, which aims to raise awareness of climate change and foster connections within local communities. Eco Showboat is led by Anne Cleary and Denis Connolly, who in 2023 began navigating Ireland’s inland waterways, engaging with local artists, scientists, and communities to inspire climate action. Their broader project was supported by Creative Ireland’s Climate Action Fund, the Arts Council of Ireland, SFI Discover, LAWPRO, and Waterways Ireland. In response to Cleary and Connolly’s boating journey and conceptual framework, Christine developed a project focused on the issue of water pollution in her local environment. She became particularly interested in the potential of certain plants to absorb pollutants and help restore damaged ecosystems.

Her project involved designing an experimental ecosystem that could simulate real-world environmental conditions. During her research, Christine discovered that most floating wetlands are made using plastics such as polyethylene (PE) and polyvinyl foam—materials that degrade over time and release pollutants into the water. Seeking a more sustainable alternative, she began exploring the natural resources around Glenade Lake, an area rich in willow and reeds. A book by Joe Hogan on basketmaking, along with a workshop in basic willow weaving techniques, became the foundation for her project, MESOCOSM, and inspired the creation of large-scale circular woven willow baskets.

These MESOCOSM islands now float on Blackrock Pond, serving as alternative habitats for a variety of land and water species. They function as bioremediators, helping to purify the water, and as nesting or resting stations for wildlife. In doing so, they provide safe, supportive shelters in the face of ongoing habitat loss and environmental change.

“The project draws attention to the vulnerability of ecological systems and the negative human impact, while also highlighting the creative potential for positive intervention”.

MESOCOSM afloat. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

Christine’s work in WaterLANDS

Through her years of research and work on the RIVERworks and MESOCOSM projects, Christine developed a new interest in the ability of plants to harvest pollutants or heal damaged planetary systems, enabling new forms of cultivation. It comes as no surprise that she was drawn to the WaterLANDS project for its strong scientific foundation, which resonated closely with her practice at the time.

The project allowed her to explore the complex terrain of upland and lowland landscapes alongside a diverse scientific community. Through this collaboration, she deepened her understanding of how to read these landscapes—by walking through them, listening attentively to both human voices and the rich, varied sounds of the natural world. The restoration sites Christine is working on as part of the Irish Action Site have very different characteristics. Bencroy— one of the main restoration areas—is a transitional habitat shifting from grassland to bog. It also has the Bencroy Coal Mine, an important feature for understanding the site’s geological history. Altateskin and Altachullion Upper are lowland blanket bogs shaped by artificial drainage systems and conifer plantations. These are now being actively managed and removed. Slieve Anierin, by contrast, is the most remote and difficult to access. Defined by severe erosion and complex water systems, it's one of the few places Christine chose not to walk alone due to the challenging terrain.

Field study: Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

Plotting with John and Kieran. On-site. Photo credit: Christine Mackey

“One of the unexpected aspects of this residency was discovering how accessibility varied for each of the sites. They are containers of distinct physical characteristics, diverse habitats, some have unique rock formations, and dense, plant-based terrains like deep heather, which can be exhaustingly slow to walk across. And then there’s the weather: constant rain, sloping ground, and the risk of sinking knee-deep into mud or exposed peat pools. These conditions shape not only the landscape but also the way one moves through it, listens, and observes.”

Over time, Christine realigned her focus more closely on the Bencroy site, which is currently undergoing active restoration, having been damaged by years of erosion due to weather exposure, fires and climate change. It presents a striking example of ‘bare peat’- areas where the protective vegetation layer has been lost, exposing the peat soil. Bare peat is a common issue, particularly in the uplands, as a consequence of several natural and man-made pressures, including overgrazing and fires. In many areas, bare peat is now mainly eroded by natural agents such as wind, ice or water. These bare peat areas act as sources of CO2 emissions and are accompanied by habitat loss. At Bencroy, Christine found her creative direction based on meaningful time spent with botanists on-site who carry out annual plant surveys. This led to a fascinating and rewarding collaboration with John Conaghan and Heather Bothwell—walking the bogs with notebook and pencil in hand, learning to read the landscape through their eyes. Each year, the botanists on site plotted and market out their sites to ascertain the plant communities existing in the space and looking for those that would potentially return due to the restoration.

John Conaghan on-site. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

There is no single creative approach or outcome from this work; the process is complex and multi-layered. Even the reading material—ranging from ecological theory to the politics of land ownership and restoration law—becomes part of the visual and conceptual fabric for the project. Art can go beyond the conventional form of “art-making” and commissioned work. For Christine, WaterLANDS is an opportunity to deepen, long-term, seasonal practices—allowing for ongoing research into peatlands and the restoration process, annual engagements with scientists, and the site-specific challenges that each location presents. This kind of research-driven practice is very different from a studio-based approach— and difficult to quantify, especially within institutional contexts that are often results-driven. Still, there is a common thread visible in Christine’s research, focusing broadly on two strands of direction.

Dublin Botanical Gardens Archive. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

Use of materials in the restoration process

Christine is especially interested in how artists can contribute meaningfully to the material processes of ecological restoration, and how such collaborations unfold in real-world contexts, with all their inherent challenges and complexities. As an installation-based artist and building on her previous work MESOCOSM, one of her current interests in WaterLANDS evolves around the restoration materials used at Bencroy. Coir, a coconut fibre, is formed into geotextiles, which are commonly used to cover bare peat, helping to reduce soil erosion from wind and rain. Its open weave stabilises the ground and allows seeds to take root. It’s also used to block small water channels, slowing down water flow across the bog. As coir cannot be grown in Ireland, Christine is interested in exploring locally-produced alternatives to coir, such as wools and flax. This involved learning about the different wool types, engaging with sheep farmers, and attending workshops on wool processing, spinning, and weaving. She has grown out a small plot of flax, which she plans to process into rope and string, experimenting with ways to combine it with the wool. Long-term, she believes it could be more holistic and ecologically sound to grow such materials used for restoration processes in Ireland, offering a circular economy from land to farmer to land. This could introduce a greater sense of sustainability, tactility, and locality into restoration work itself. Work that local farmers could potentially take on themselves.

Bencroy. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

Material experiments, woven flax, seaweed and wool. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

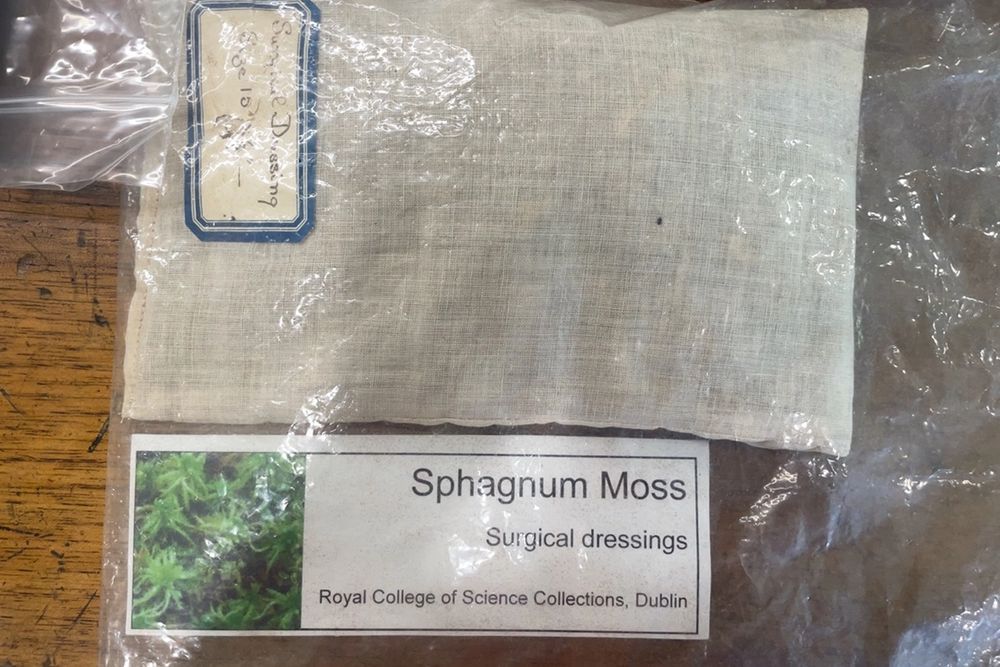

The microscopic world of Sphagnum

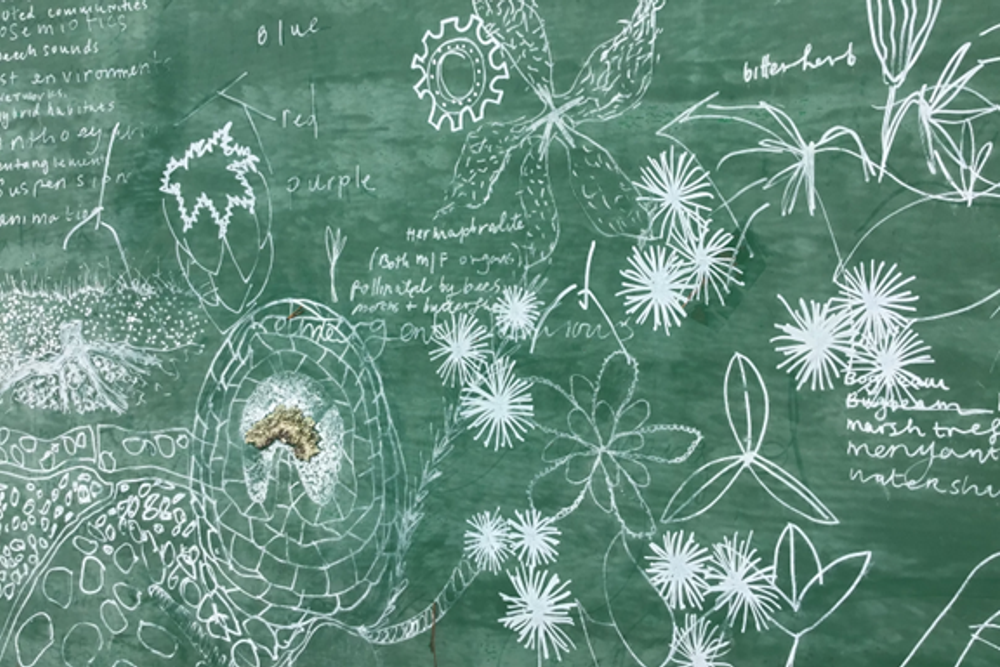

The second aspect Christine is exploring is Sphagnum moss – known as the bog builder of peatlands because of their ability to absorb and store large volumes of water while keeping conditions acidified. Sphagnum mosses host a diverse community of microscopic life and support creatures like insects and amphibians. Bacteria that live on its surface play a vital role in breaking down methane and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The ongoing creative challenge for Christine is to visualise these organisms – possibly through drawing or print.

Drawing exploration of microscopic worlds hidden in Sphagnum. Photo credit: Christine Mackey.

Christine has an ongoing independent arts practice that involves many projects and engagements that all tend to flow and inform each other. Some of her other projects have informed her work in WaterLANDS and vice versa. One-to-one engagements with local sheep farmers in Leitrim, for instance, have provided her with new insights on the production, value and use of wool. These discussions have given her new food for thought on finding other ways for the material to be reused imaginatively, providing new insights into her research in WaterLANDS. Christine aims to continue her research into such material processes long-term through future restoration projects in Ireland.

Learn more about Christine’s work as part of WaterLANDS here.